The butterflies that I stop and look at are usually very large and made of grid cloth. Here’s what I use overhead in daylight exteriors, and when.

Making actors look good outdoors can be really difficult. When possible I try to schedule outdoor shoots for morning or afternoon so as to avoid mid-day “raccoon eyes” that make actors look… well, unpleasant at best. This isn’t always possible, however, and as we’re responsible for getting the shots the director needs no matter what it’s important to know how to keep moving forward regardless of how ugly the ambient light is.

Making actors look good outdoors can be really difficult. When possible I try to schedule outdoor shoots for morning or afternoon so as to avoid mid-day “raccoon eyes” that make actors look… well, unpleasant at best. This isn’t always possible, however, and as we’re responsible for getting the shots the director needs no matter what it’s important to know how to keep moving forward regardless of how ugly the ambient light is.

Actors tend to look best in backlight where the sun is no higher than about 60 degrees, or low enough that it doesn’t creep over the top of their head and light up the tip of their nose. Front light is a little tougher—if the sun is higher than about 40 degrees it won’t reach into deep eye sockets and shadows become very dark and contrasty.

IT’S ALL ABOUT CONTRAST

The higher the contrast between highlights and shadows the more precisely lights must be placed. Hard light on faces can look great but only if it’s coming from exactly the right spot, and that varies from face to face. DPs had the luxury of lighting every face perfectly in the 1940s and 1950s but schedules and directorial styles no longer allow for that kind of precision. One way of fixing a situation where the light isn’t hitting an actor perfectly is to reduce contrast instead.

The thing to understand is that contrast is less important on wide shots than on closeups. I’ll let things slide on establishing shots that I’d never allow on closeups, but closeups tend to be a lot faster and easier to clean up.

THE BIG BOUNCE

This is the fastest and easiest way to control contrast. Big bounces—anything from 4’x8′ foam core or 12’x12′ or 20’x20′ gryffs— spread soft light across a large area and are generally soft enough to feel “invisible” (they don’t cast obvious shadows). Their one giveaway, though, is that they create large soft highlights in flesh tone that generally look great but reveal that you’re using a large bounce source as fill light. One way around that is to underexpose the fill source by a stop or more: darker tones tend to be more forgiving than brighter ones. This may be because their defining characteristics—hard light vs. soft, directionality, and sometimes color—are slightly obscured in the shade whereas brightness makes imperfections jump out a bit more.

I’ll often underexpose day exterior fill to the point where flesh tone looks like a dark tan. As long as the talent’s eyes are visible I’m happy to shoot. The most important thing for my taste is to reduce the contrast between the eye sockets (in shadow) and the nose (in sunlight). If the actor looks like a raccoon in closeup then I’ve not done my job.

Different bounce sources have different characteristics. Foam core is a little shiny and can cast a subtle but hard shadow, so I’ll often use bead board instead: its surface is made of perfectly matte styrofoam beads that radiate very soft and non-specular light. Gryffs can be a little shiny as well, so given the time I’ll cover them with another material, like silk or muslin, to give them a matte finish.

I’m a little different in that I’ll often use a big bounce on the same side of the subject as the sun when possible. For example, if an actor is edge lit by the sun on the camera right side of their face then I’ll put the bounce on the right side of the camera. That has the effect of “wrapping” the sunlight around their face, creating a range of continuous tones from highlight to mid-tone to shadow. Even if I can’t do this, however, I’ll try at the very least to keep the bounce source near the lens so I can push it into both eyes and hide its shadow so it feels “invisible.”

There’s nothing that says a bounce source has to stand vertically. When I was a young camera assistant I saw a very good DP create beautiful fill light by laying sections of bleached muslin on top of black asphalt. The road surface sucked up a lot of light and left eyes very, very dark but the placement of squares of muslin on the road surface just out of frame filled eyes in nicely and felt very natural.

OVERHEADS: WHAT I DON’T LIKE

I hate silks.

Poly silks are just too heavy for my taste. They reduce exposure by several stops, requiring either overexposing the background or adding bounce fill under the silk, and they have a very distinctive look that reminds me of TV shows from the 1980s. (Yes, I remember a lot of TV shows from the 80s. If you want to see sloppy and fast work, watch TV shows from the 70s and 80s. Blech!)

China silks are slightly less offensive as they are thinner and preserve the directionality of sunlight while making it a little bit less harsh, but they too have a very distinctive look that I feel is overused. The larger sizes often have seams, and as china silks are thin the seam itself can cast a shadow that’s a dead giveaway that a rag is flying overhead. I’m not a fan.

OVERHEADS: WHAT I DO LIKE

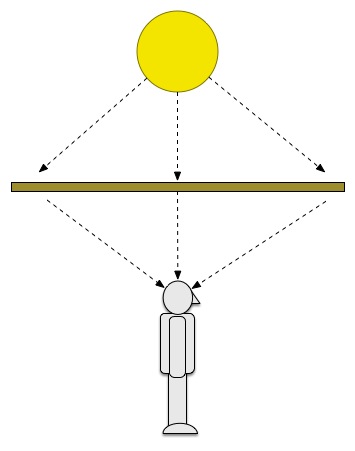

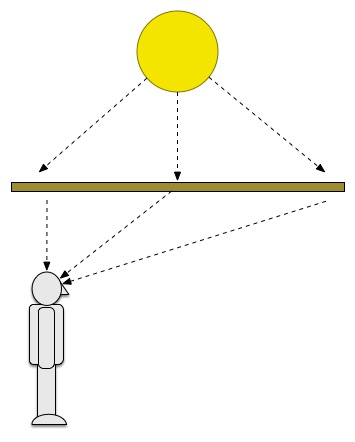

This depends on the environment. If I’m working out in the open I love either half soft frost or Hi-Lite. Both of these resemble translucent shower curtain material. They’re great for making the tiny ball of sunlight in the sky look a lot bigger from the perspective of anyone standing underneath it. If I look up at the sun through half soft frost the hot spot expands in size by 5-10 times. This preserves the direction of the sunlight while softening hard shadows considerably. Exposure under half soft frost or Hi-Lite only drops by about a half stop so the background doesn’t look overexposed.

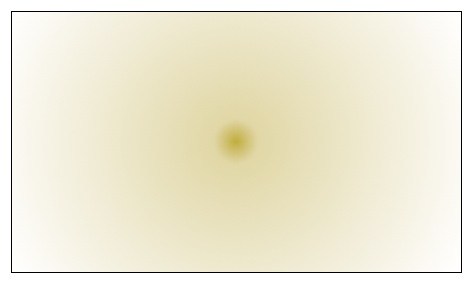

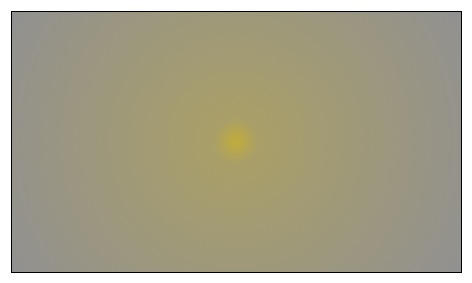

This is what the sun looks like when I look at it through very light diffusion, like a thin silk. The ball of the sun spreads a little bit, softening cast shadows, but it's still a pretty hard source.

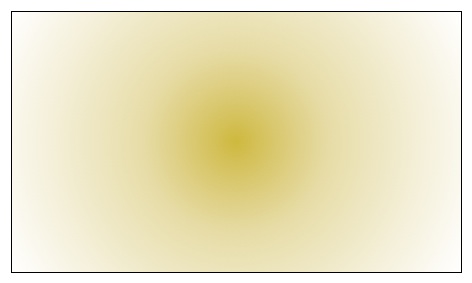

This is what the sun looks like through half soft frost or Hi-Lite. There's still a hot spot—a "specular" source—but it's a lot bigger than the actual sun is, and this softens shadow edges considerably. Sunlight retains its directionality while becoming kinder to faces.

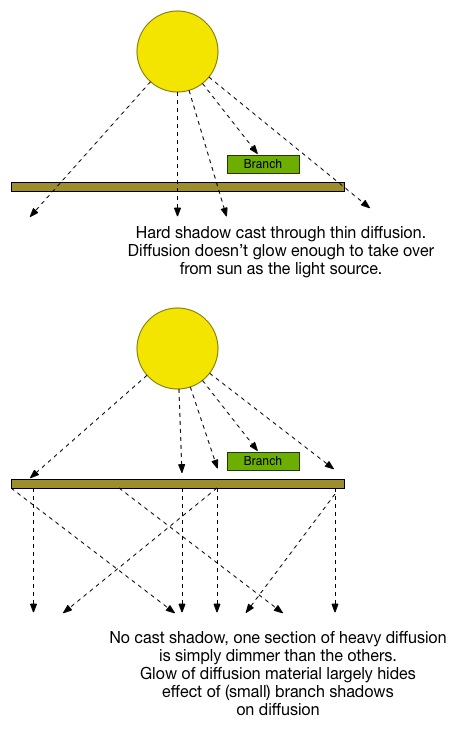

These two diffusion sources—half soft frost and Hi-Lite—make the sun appear a bit bigger but they don’t replace it the way a really soft source does. There are times when thick diffusion, such as half grid or full grid cloth, comes in handy. Years ago, while shooting under some trees, I found that the contrast between the sunlight coming through the branches and the shade was way too high. I had my crew rig a 12’x12’ half soft frost over the actors. Mistake! The translucent diffusion retained enough specularity that I still had shadows wherever a branch blocked sunlight above the frame. I didn’t reduce the contrast between sun and shade at all, I just made the shafts of sunlight a little softer. The shadows themselves were still too dark.

There are two kinds of diffusion: those that soften the source, and those that become the source. In this case I needed diffusion that became the source, and half grid cloth was the answer. Grid cloth doesn’t really “soften” light because it doesn’t pass any hard light at all. Instead it glows and becomes a very soft light source itself. After swapping out the light half soft frost for the heavier half grid cloth I walked under the diffusion and never felt like I was in shadow because I couldn’t see the the sun as a hot spot anymore, I only saw the glowing white diffusion broken up by occasional branch shadows.

The effect is similar to bouncing light off a ceiling but pushing it through a cucoloris first: you’d see shadows on the ceiling but there’d be nothing but soft light hitting the actors.

Top: thin diffusion. Bottom: thick diffusion. Thin diffusion will pass shadows if anything comes between it and the light source. Thick diffusion becomes the light source, so shadows don't pass through—they just make part of the diffusion a little darker.

Thick diffusion has its own look that can often give it away, particularly if actors stand directly under it and appear obviously top lit. I’ll often try to put the rear of the butterfly over the actors so most of the lit surface extends toward the camera. That way most of the light from the diffusion strikes them from the direction of the camera rather than immediately overhead.

In this position thick diffusion can still cast eye shadows and feel like an artificial source suspended overhead.

Placing the actor at the back of the diffusion means most of the light comes from the direction of the camera, filling in eye sockets and making the light a little less visible. Underexposing the fill by a stop or so can further sell the effect.

OVERHEADS: LOW BUDGET SUBSTITUTIONS

A good replacement for half soft frost is clear plastic drop cloths meant for painting. They’re easily found in huge sizes at hardware stores. Various thicknesses spread light in different ways.

Grid cloth is easy to find at fabric stores. Some stores call it sail cloth.

Bleached muslin may work as well, although it still passes a bit of specular sunlight. It’s more like silk than shower curtain.

OVERHEADS: WHAT I HAVEN’T TRIED

I’ve long heard rumors from Hollywood of butterflies made of black silk and dark or neutral gray grid cloth. I worked with a crew once that used black grid cloth as a lightweight version of duvetine, normally used to block the sun when shooting exteriors, and it didn’t work very well at all as it still passed a fair bit of sunlight, but it would have been an interesting alternative to an overhead silk had I needed one. It has a combination of specularity and subtle fill that gives a little kick to skin and shiny surfaces without feeling artificial.

Dark diffusions dramatically change the ratio of specular light to radiant light.

Diffusion materials are defined by the ratio of how much hard light they pass (specularity) and how much they themselves become the light source. Black silks and dark grid cloths retain specularity while reducing the contrast between hard and soft light. The look is very interesting and natural, and I look forward to trying them some day. (They’re somewhat of a special order in my market.)

WHEN BUTTERFLIES LAND

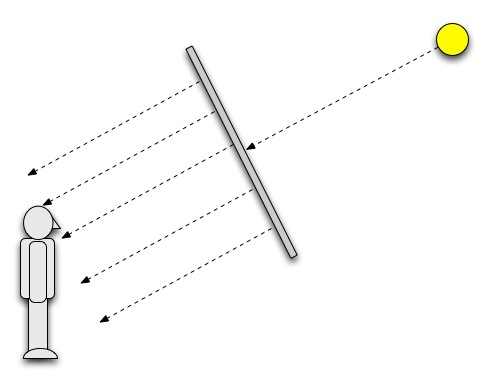

Using butterflies in the middle of the day is pretty straightforward. Any time the sun exceeds 60 degrees of height as backlight, or is higher than 35-40 degrees as front light, I usually try to fly something overhead. Occasionally, though, the sun is too low for an overhead and yet the actor’s eyes still look dark. In these cases I’ll use a lighter diffusion between the sun and the actor but set it vertically to try to open up the shadows in eye sockets.

Low thin diffusion can spread sunlight just enough to get into deep-set eyes and clean up front-lit faces.

Actors always have to look good, and the sun doesn’t always cooperate–but we can’t stop shooting and wait for it to move into the proper position. Our job is to keep the trains running on time, and the right diffusion material in the right frame at the right time goes a long way to making both us and the actors look good.

About the Author

Director of photography Art Adams knew he wanted to look through cameras for a living at the age of 12. After spending his teenage years shooting short films on 8mm film he ventured to Los Angeles where he earned a degree in film production and then worked on feature films, TV series, commercials and music videos as a camera assistant, operator, and DP.

Art now lives in his native San Francisco Bay Area where he shoots commercials, visual effects, virals, web banners, mobile, interactive and special venue projects. He is a regular consultant to, and trainer for, DSC Labs, and has periodically consulted for Sony, Arri, Element Labs, PRG, Aastro and Cineo Lighting. His writing has appeared in HD Video Pro, American Cinematographer, Australian Cinematographer, Camera Operator Magazine and ProVideo Coalition. He is a current member of SMPTE and the International Cinematographers Guild, and a past active member of the SOC.