A gaffer once called me a “picky lighter.” I take pride in that designation, but I also take pride in working fast. Here’s a new soft light trick I’ve been thinking about.

I have one goal when it comes to lighting: do great work fast. I’m also a sucker for soft light. I can’t get enough of it. I love contrast, and I love bringing out form and shape through lighting, but I naturally lean away from hard sources and toward very diffuse materials and matte reflective surfaces. Hard light has its place, but outside of sunlight I don’t see harsh shadows very often in the real world. I love the subtle shading of a soft light source.

The trick with soft light is that it generally takes a lot of space to create. Pushing light through diffusion, for example, requires a frame of diffusion with a light behind it, and if the beam of the light is too narrow then it’s necessary to back it up enough so that it fills the entire diffusion frame. (Using less than the entire diffusion frame is a bit of a waste as you’re creating a smaller source than you could, although there are times when that’s useful.) Bounce sources are the same: there has to be some distance between the light and the bounce material to ensure that the entire bounce source is evenly lit.

I obsess a lot more over diffusion than I do bounce sources, because very few diffusion materials are thick enough for me. I love Lee 129 and 1000H tracing paper because they don’t pass any specular light at all: this not only makes them very soft but creates beautiful glowing specular highlights in shiny surfaces and human skin. Lee 216, 250 and 251 (opal) have their uses, but when I’m lighting faces in close quarters I prefer the thickest diffusion possible.

Bounce sources are easier. They’re almost always softer and don’t require much additional effort. Lighting through diffusion often means projecting more light into the set, but if light levels aren’t a priority bounces are always softer and more forgiving. The trick, though, is that I’m starting to become really picky about the quality of my bounce materials, and foam core just isn’t good enough anymore. I’ll still use it, but I want something softer and less specular.

Foam core (in Europe, “poly”) has a little bit of a shine to it, which makes it directional (occasionally useful) but also casts a little bit of a hard shadow (frequently less useful). A common trick is to cover foam core with bleached muslin, which is a wonderful bounce material because it’s not shiny at all: hundreds or thousands of cloth threads scatter the light everywhere with zero specularity. I’m also a fan of Ultrabounce, a very white and very matte material that’s fairly common to the industry now. I’m always interested in low tech answers to common lighting problems, though, and I think I’ve come up with something slightly novel.

Book lights are a great way to create the softest light possible on a set but they can be a bit unwieldy. Most often they consist of a bounce source with a large piece of diffusion rigged in front of it. The combination of bounce plus diffusion means that the diffusion becomes a perfectly even source, free of a hot spot, that casts soft shadows with very gentle transitions from bright to dark.

The problem is that standard book light configurations can be a bit unwieldy to move around. A 8’x8′ booklight, for example, typically consists of an 8’x8′ bounce in one frame, 8’x8′ diffusion in another frame or hung from speedrail on a stand (“T-boned”), and a light. My goal: reduce the number of moving parts to make book lights faster to set up and move around.

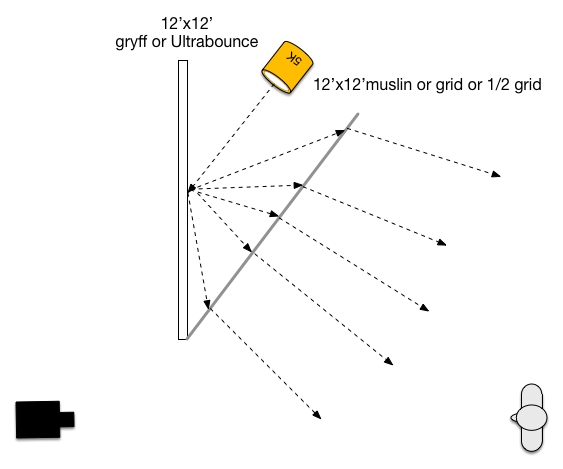

Here’s the standard method:

In this case there’s two frames and a light to move around, plus the open side of the frames must be controlled with flags or duvetine.

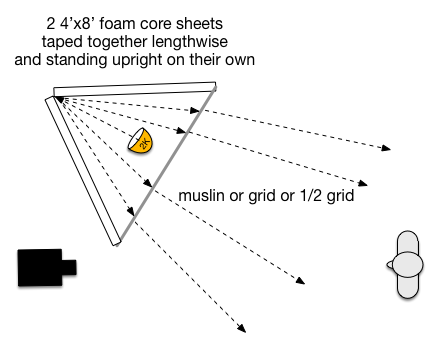

This method is a little more practical:

Still photographers use “V-boards” quite a lot, but they’re a relatively new addition to the film industry. This configuration mirrors a Westcott soft box I’ve used for still portraits, where a flash illuminates the interior surfaces which then radiate forward through grid cloth or other thick diffusion. Sometimes a soft light needs to move six inches to the left, which would be a little bit of a hassle as there are still three components (bounce, diffusion and light) that have to move.

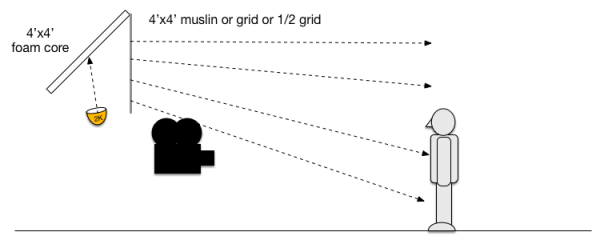

On a recent commercial I needed a soft 4’x4′ source in a tiny space, and my crew built a small book light out of an angled 4’x4′ foam core bounce with a frame of Lee 129 angled into it. The open part of the book light faced down, with the light on a low stand aimed up into the bounce card. I really liked this setup, and it got me thinking: how can I do this faster and with fewer stands?

I came up with this:

The bounce is a 4’x4’ piece of foam core, bead board (which has a beautiful matte finish), gator board or any other common bounce material. The front diffusion can be any cloth that’s reasonably thick: ½ grid cloth, muslin, etc. The cloth is taped to the top edge of the diffusion frame and held in place by gravity.

In theory this should work quite well. I think I’m going to opt for bleached muslin as my fabric as it’s cheap and it worth well both as a matte bounce and diffusion. The fabric can be clipped flat to the front of the card and used as a very soft bounce, but tipping the card forward, releasing the clips and moving the light to a steeper angle turns it into an instant book light.

This also solves a problem that pops up with bounces in tight spaces: crews will often tip the bounce card forward and light them from below, but the steep angle means the bottom of the card ends up much brighter than the top. This effectively turns the bounce card into two sources: a bright 2’x4′ light (at the bottom of the bounce card) adjacent to a dimmer 2’x4′ light (at the top). This might be desirable in some circumstances as the cast shadow might appear more complex and random (and therefore more natural) but it probably isn’t as kind to faces. Putting a layer of diffusion in the way blends these two sources together.

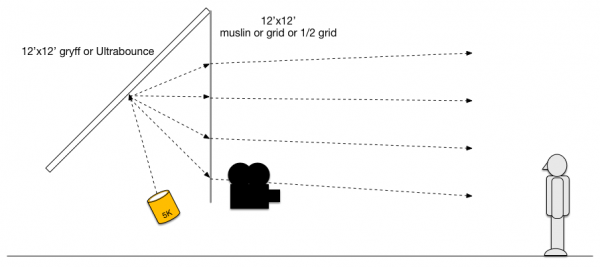

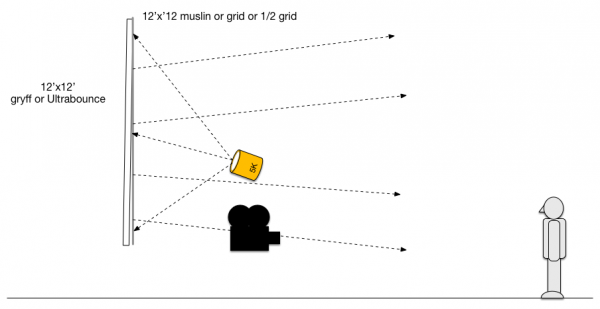

In theory this same technique can be used with larger bounces as long as you’ve got the room to tip them. For example, here’s a 12’x12’ gryff with 12’x12’ muslin hanging off the front of it:

It’s not uncommon to put muslin in front of a gryff as gryffs tend to be a bit shiny anyway, and while muslin is a great bounce material it does let quite a lot of light pass through. The gryff redirects the transmitted light back through the muslin, making it more efficient. Since this is a common configuration anyway it seems simple to release the muslin from the frame on three sides, leave the top attached, tip it forward a bit and put a light or two underneath. Voila: instant book light.

Although this setup seems simple I suspect it’s deceptively so. When I’ve built small booklights common diffusions I’ve found that they can be curiously directional: for example, Lee 216 is generally considered thick diffusion but it’s transparent enough that I can see the glow of the bounce card through it, which means that if I move too far off angle and I can’t see the glow anymore then I’m no longer receiving light. My ideal book light is essentially a big, square china ball, so I’ll have to experiment and see at what point the diffusion truly becomes the light source instead of simply being a diffuser.

I haven’t tried this yet but I hope to shortly. I’ll have to send this article to my regular gaffers as a warning that I’ve got yet another crazy lighting scheme that I want to try.

About the Author

Director of photography Art Adams knew he wanted to look through cameras for a living at the age of 12. After ten years in Hollywood working on feature films, TV series, commercials, music videos, visual effects and docs he returned to his native San Francisco Bay Area, where he currently shoots commercials and high-end corporate marketing and branding projects.

When Art isn’t shooting he consults on product design and marketing for a number of motion picture equipment manufacturers. His clients have included Sony, Arri, Canon, Tiffen, Schneider Optics, PRG, Cineo Lighting, Element Labs, Sound Devices and DSC Labs.

His writing has appeared in HD Video Pro, American Cinematographer, Australian Cinematographer, Camera Operator Magazine and ProVideo Coalition. He is a current member of the International Cinematographers Guild, and a past active member of the SOC and SMPTE. His website is at www.fearlesslooks.com. Find him on Twitter: @artadams.