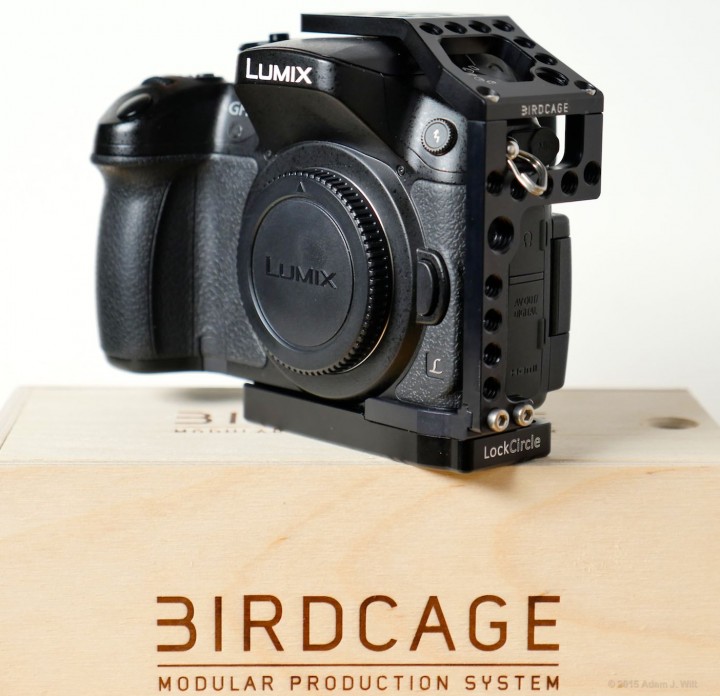

This post is a two-parter: the rationale behind camera cages in general; and a review of one such device, the BirdCage swivel, that I bought for my Panasonic GH4.

Camera cages?

Camera cages are metal exoskeletons designed to wrap around DSLRs, mirrorless cameras (a.k.a. Compact System Cameras or CSCs), and the like. They have several main purposes:

- They make the camera much more rigid, so that the body won’t flex and wobble when you do something as simple as focus a lens.

- They add multiple attachment points for accessories.

- They protect delicate HDMI ports.

Let’s examine these one at a time.

Cages make the camera more rigid: Still cameras have lightweight tripod sockets designed largely for one purpose: to keep the camera from falling off the tripod. They are suitable for holding the camera still, more or less, assuming there’s no substantial disturbance. In this context, a “substantial disturbance” can be something as simple as the slap of a DSLR’s reflex mirror flipping up and then down again; that’s why many DSLRs have a mirror lockup function. For still photography, this is adequate.

For motion work, the limitations of such a mount become apparent: grabbing the lens to zoom or pull focus, or focusing with a follow-focus mechanism, may show up in DSLR/CSC video as a wobble or bobble.

Cranking a follow-focus doesn’t so much spin the ring as push the focus gear up and down. Any drag in the focusing mechanism transmits those pushes to the lens and camera body.

The problem is that a typical still camera’s body, and its attachment to the tripod, aren’t particularly rigid: the mere act of touching the lens, or turning the focus ring with a follow-focus, can warp the body and/or flex it slightly on its mount.

Actually, there are two other main sources of such wobble; the squishiness of the body is only one factor.

Common bayonet mounts like MFT, E-Mount, Canon EF, Nikon F, etc. are also “soft” in that the lens is held in place by leaf springs. Applying even a slight force to the lens body can shift or rock it on its mount, sometimes subtly, sometimes not. (By contrast, a breech-lock mount like PL, or the C500‘s EF mount, uses a cam-driven lockring to clamp down on the lens flange, fixing the lens rigidly in place.)

Some tripod plates or adapters are inherently wobbly, too, in that they have a layer or mat of rubber or plastic—this protects the camera’s baseplate from scuffing and reduces the tendency of the camera to rotate on the screw, but it’s soft enough to compress when the camera is pushed, allowing it to wobble.

A cage can’t protect you from shifty lenses in bayonet mounts (unless they accommodate rigid lens adapters; of which more will be said below), or from rubbery tripod plates, but they can firm up the camera body itself. They do this by pinning the camera in at least two places: the tripod socket on the bottom and the accessory shoe at the top. By forming a rigid exoskeleton with its own tripod socket milled into a substantial baseplate, and securing the camera at both top and bottom, a well-designed cage imparts substantial stiffness to an otherwise flexible camera.

About those shifty lenses: some cages connect to or support add-on lens adapters, such as MFT-to-PL or E-to-PL adapters. Attaching a lens adapter to a cage extends the exoskeletal support to the lens mount itself, so the lens isn’t entirely dependent on the stiffness of the camera’s own lens mount. Adapters for larger bayonet types, like F or EF, also benefit from the enhanced rigidity; the leaf springs in these larger mounts are still subject to compression, but they’re usually more robust than the springs in the camera’s native MFT or E-mount.

Cages add multiple attachment points for accessories: DSLRs/CSCs are well provisioned to handle a single accessory, in the shoe mount on top of the camera. Beyond that? Not so much.

Cages are the cheeseplates of the DSLR/CSC world. They add multiple 1/4” and 3/8” tapped sockets for mounting mikes, lights, audio recorders, articulated arms, external monitors, and the like. Many offer one or more shoe mounts, too; for those that don’t, there are bolt-on shoe mounts that attach to 1/4” sockets.

Some cages include (or can be fitted with) rod attachments, top handles, NATO rails, rosettes, bespoke battery plates… in essence, if there’s a way to hang a bit of gear on a cine camera, someone makes a cage that’ll let you hang that same bit of gear on a DSLR or CSC.

Cages protect delicate HDMI ports: The mini- and micro-HDMI ports used on many DSLR/CSC-style cameras are notoriously fragile. In some cases all it takes is one good yank on the cable to damage the port beyond repair.

Many cages offer armored HDMI port adapters, affixed to the cage itself, to take the load off the fragile internal connection. Often the adapter’s port is a full-size HDMI socket, which tends to be sturdier than the smaller connector on the camera’s body. Not only does the cage’s adapter provide a more robust connection, it’s more easily replaced if it does get damaged or destroyed.

Even if a cage does’t have a custom HDMI adapter, it’s a handy place to tie-wrap, velcro, or gaffer-tape a strain-relieving loop of cable—a trick that works for all the various cables that wind up dangling off a camera.

Downsides

Cages make your camera bulkier and heavier. They can block access to controls and ports, or make them more awkward to use. They may make it more difficult or less comfortable to handhold the camera.

Some cages leave the right side free, so you can use the camera’s own handgrip, but they may not be as rigid as a fully wraparound cage.

Some cages are custom-designed for a specific model of camera: when that body style becomes obsolete, so does the cage. Conversely, others are universal designs that can move from camera to camera—but they may not fit your camera quite so well, or they may not embrace it so rigidly.

A very brief trawl of the web shows cages running from $95 to $795, and I don’t claim to have captured the full price range by any means. Let it suffice to say there are a lot of choices out there. If you decide you need a cage, you’ll have options; just keep in mind the various advantages and disadvantages that the different designs have. Perhaps my experiences will serve as a guide…

Caging the GH4

Before I had manually focusing primes I was as carefree as they come: I’d pop my GH4 with its stock Lumix lenses onto my tripod, and I was good to go.

The Lumix G-series glass is optically superb but operationally hopeless from a serious-filmmaking perspective: the unmarked fly-by-wire focus mechanisms mean that repeatable focus pulls are impossible, so I’d pre-focus the lenses for a fixed-focus shot and then leave the lens alone. Thus my tripod shots were smooth and stable… if a bit limited in depth changes. (In handheld run’n’gun, I’ll focus by eye and rock through to find my focus point, but I’ll allow focus hunting and wobbly images in handheld work that I refuse to put up with in studio-style tripod shooting.)

I obtained a Voightlander Nokton 25mm f/0.95, and then a set of Veydra mini primes, because I really like being able to focus properly. These are manual lenses with a decent amount of focus-ring drag; focusing by hand imparts a fair amount of wobble to the shot, and spinning a follow-focus rapidly pushes the lens around noticeably.

It didn’t matter how firmly I screwed down the camera or locked the tripod’s knobs; anything more than the faintest touch flexed the camera on its mount and bobbled the shot. The GH4 has many strengths, but rock-solid rigidity is not one of them.

I’ve also had the occasion to mount more than one thing at a time on the camera, like a microphone and an external monitor/recorder. With the mike in the shoe mount, I’ve wound up using an articulated arm, a 1/4”-to-15mm-rod adapter, and my follow-focus rails, even when I’m not using a follow-focus; I’ve also set up a second tripod just for the monitor/recorder. Either way it’s a bit of a kludge, and it displeases me.

I reluctantly started looking at cages. I wanted something small and compact, so I could still stuff the caged GH4 into my pack for travel. I needed one that left the handgrip free since I didn’t relish the idea of uncaging the camera every time I wanted to get a handheld shot. Whatever I found had to allow the flip-out monitor to tilt and swivel to its fullest extent.

There’s a good overview of cages fitting the GH4 at dslrvideoshooter. I was intrigued by LockCircle’s BirdCage swivel, as it seemed the closest fit to my needs, but I found the price distressing (I’m a cheap bastard). I was also concerned about the cage’s rigidity: the narrow vertical link, needed so the monitor can pivot, would likely reduce the BirdCage’s stiffness. Then I stumbled upon their “bargain” page and saw a BirdCage for 30% off, which dulled the pain enough to take a punt on it.

Within 48 hours of placing the order, a FedEx package arrived from Italy. It contained a slide-top wooden box:

The box contained 98% packing peanuts, and 2% the bits to make up a BirdCage, a hex wrench to assemble it with, spare screws, and instructions:

The assembled cage uses a separate, thick baseplate to affix it to the camera; that baseplate can be swapped with ones that attach Metabones or P+S IMS adapters for F, EF, or PL mount lenses. The top of the cage screws into the camera’s shoe with the supplied clamping plate:

On first fitting, I found that the GH4‘s left-side strap lug prevented the cage from aligning properly with the camera:

I popped off the plastic insert on the wire “loop” so that I could rotate it out of the way, and then the BirdCage fitted properly against the camera. The plastic insert is undamaged and can be reinstalled in the future if and when the camera comes out of its cage.

The baseplate, with dozens of holes to add lightness without removing stiffness, screws into the GH4’s tripod socket, clamping the base of the cage firmly against the camera. It has its own 3/8” socket and comes with a 1/4” adapter, as shown. It’s cut away at the side so you can change batteries with the cage in place.

The cage’s top plate, screwed into the shoe, immobilizes the top of the camera (and prevents the flash from opening).

Fully assembled, the BirdCage doesn’t bulk up the GH4 excessively.

The swivel model doesn’t offer an HDMI adapter because the adapter prevents the screen from swiveling (there’s another BirdCage with an HDMI adapter, but no swiveling). I tie-wrapped a micro-HDMI-to-full-HDMI cable in place instead.

How well does it work?

It works superbly: my soft, squishy GH4 is now a solid and substantial camera. My worries about the rigidity of the BirdCage were unfounded; the metal bits are beefy enough to eliminate any tilting and rocking of the camera body itself.

When I mounted the caged GH4 on my $150 rail kit (I said I was a cheap bastard, didn’t I?) and cranked the follow-focus vigorously, the front of the lens rose and fell perhaps a third as much as it did with the uncaged GH4.

But still, the lens rose and fell. Half of that turned out to be the squishy rubber pads on the camera plate, and half was residual play in the lens mount itself.

I tried moving the camera from my rail kit directly to the metal-surfaced top of my Miller fluid head, and compared its compliance with that of the uncaged camera by pushing the lens up and down by hand, as well as by grabbing the lens and pulling focus directly.

I wasn’t able to see any motion of the camera body itself; it was locked solidly and immovably to the top of the tripod. The small remaining bobble came entirely from the lens mount itself, detectable by laying a finger along the lens-to-body join and feeling the lens squirm slightly as it was manipulated.

When I popped the camera out of the cage (it takes only half a minute to do so) and bolted it directly to the fluid head, the camera bobbed and swayed like a drunken sailor in his last conscious moment of shore leave; I didn’t have to look closely to see the difference!

I moved the camera back into its cage and remounted it on the rail rig, this time screwing it down with what would have been excessive force had I been using the camera’s own tripod socket. By really compressing those rubber pads, I was able to stiffen the cage-to-rig interface enough to remove most of the play, so that the only significant remaining wobble source was the squishiness of the MFT mount.

Here’s a comparison of focus flexing, with and without the cage: I’m cranking the focus whip as fast as I can to exaggerate the flexing. Yes, there’s still some wobble with the cage, but it’s mostly in the squirming of the lens on its mount, plus a little bit of squish in the rubber pads on the rod kit’s camera plate (in both cases, the camera mounting screw has been tightened the same).

Focus flex with uncaged GH4

In short, mission accomplished. The formerly-flexible camera is now a stiff and solid structure, with plenty of places to attach accessories. Yet the camera isn’t much heavier or bulkier than it was before; it’s still eminently handholdable; and the flip-out monitor isn’t blocked or limited at all.

Perfection? No. The left-side mode dial is difficult to turn as it’s nestled beneath the top plate. The MIC port’s cover is harder to flip open, and the surrounding structure prevents mikes with right-angle plugs from connecting directly without an extender. The left-side strap lug’s function is impaired somewhat, and the camera’s flash can’t be opened. And while this BirdCage fits the GH4 (and the GH3) like a glove, it won’t fit another camera: if the future GH5 draws me like a moth to the flame, and has a different form factor, the BirdCage will be consigned to the dustbin of history (or more likely will be sold along with the GH4 it’s wrapped around: time, like an ever rolling stream, bears all its sons away).

For my purposes, these deficiencies are less important than the structural improvements the BirdCage brings, while meeting my needs for compactness, handholdability, and full use of the tilt-and-swivel monitor.

Your needs may be different, in which case a different cage (or no cage at all) might be the better way to go. A cage is like clothing for your camera; it’s possibly the most “personal” accessory you can get, so it makes sense to consider your camera’s lifestyle and choose a cage to complement it.

Conclusion

If you find your DSLR, CSC, or similar camera is wobbling around annoyingly when you’re trying to zoom or pull focus, and/or you have more stuff to hang on the camera than it has mounting points for, you may want to wrap the camera body in a cage. Combining the functions of exoskeleton and cheeseplate, the darned things actually do work (at least the BirdCage does), substantially stiffening squishy-bodied cameras and providing a plethora of mounting points.

Cages come in a wide variety of sizes, shapes, and prices, with differing features catering to differing needs. Carefully consider how you actually use your camera, and how different cage designs help and hinder those uses, and you’ll be well-placed to make an intelligent choice.

For my needs—camera stiffening without adding bulk or weight; unimpeded handheld use; no restrictions on the tilt-and-swivel monitor—I took a chance on the BirdCage swivel GH4 kit, and I’m happy with it: I’d buy it again.

May you be similarly satisfied with whatever you choose.

Disclosure: I bought an open-box BirdCage swivel GH4 kit at the full “bargain” price using their website shopping cart; I didn’t tell LockCircle I would be writing a review, nor did I get any special consideration or pricing from them. There is no material connection between me and LockCircle.