On heels of my recent article/brain dump on lenses, here are some thoughts on filters: why they’re good, when they’re bad, and why digital filters never look the same.

Filters never add, they always subtract. For example, a warming filter passes warm light but blocks/absorbs cool light. It doesn’t add warmth, it subtracts coolness.

Filters never add, they always subtract. For example, a warming filter passes warm light but blocks/absorbs cool light. It doesn’t add warmth, it subtracts coolness.

When you use glass in front of a lens you are working at the full bit depth of the sensor (16 bit color, more or less). As soon as the signal hits the DSP the bit depth is reduced, and by the time the image gets encoded it is reduced again. Applying a digital filter to eight or ten bit footage will never look same same.

And, actually, applying a digital filter to 12- or 16-bit raw will never look the same either. Optics are too complex to emulate in software. You can create software looks that are close, and are pleasing, but they’ll never match the looks possible using their digital counterparts.

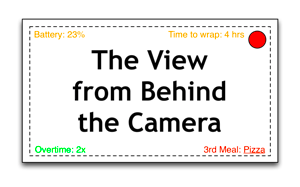

I avoid using digital filters when possible. Many directors are afraid to commit to a baking in a filter’s look on set, saying “We can always do that in post.” The two problems with that are: (1) The look will be applied without you being present, which means that someone skilled in manipulating images in a computer will apply it instead of someone gifted in the art of cinematography/photography; and (2) as digital filters require render time, and render time costs money, 90% of the time the filter will never be added.

In matte box order:

- Diffusion belongs closest to the lens. Sometimes there are dots/microlenses/textures that will come into focus under certain circumstances, and putting that closest to the lens will help obscure that.

- Hot mirrors belong farthest from the lens. These tend to be shiny, so you don’t want them behind another filter as they’ll kick reflections onto the filters in front of them.

Circular polarizers are not called that because they are circular. A polarizer works by polarizing light–passing light polarized in only one plane–and this can interact with some three-chip camera sensor blocks, as the color filters used polarize the light somewhat as well. The solution for this is to un-polarize the light on the back side of the polarizer by giving it a circular “spin.” That’s what circular polarizers do. Linear polarizers don’t do this. (This is really only an issue on older three-chip cameras like the Sony EX1 and EX3, although DSLR autofocus systems can be thrown off by linear polarizers as well.)

Polarizers work great for exteriors. They make skies blue if you’re looking at them in a specific way: 90 degrees to the sun. Point your finger at the sun and stick out your thumb, then rotate your hand around your pointed finger. Anywhere your thumb points the polarizer will works it’s magic. Also, grass reflects the blue in skylight so using a polarizer to eliminate that reflection makes grass green.

Last but not least, if a person is backlit by the sun (always the best way to shoot) and the kick off their hair or skin is too much, a polarizer will often tone that down considerably.

Color correction filters aren’t terribly useful these days as we’re all shooting HD, but there are some circumstances where they come in handy. RED M and MX sensors really hate tungsten light, so the closer you can push them toward daylight the better color you’ll get out of them. For that reason I carry 80C, 80D, 1/8 CTB, 1/4 CTB and 1/2 CTB filters with me on RED shoots. I use the one that gets me closest to daylight without costing so much light that I’m shooting wide open. Often 1/4 to 1/2 correction to daylight makes enough of an improvement.

Color correction filters can often improve noise characteristics in extreme situations. If you find yourself working under very warm (warmer than 2900K) light your blue channel can become extremely noisy. Using a light blue filter will block some of the warm light and increase the exposure in the blue channel by forcing you to open up the aperture.

Diffusion filters affect one or more of three areas: contrast, resolution and halation. Some filters work more on some than others. Soft F/X primarily affect resolution but not contrast or halation; black ProMists affect resolution and contrast but don’t halate much; and white ProMists affect all three. Once you understand this it becomes much easier to choose a diffusion filter based on what they do and what your goals are.