On the first of June, Panavision introduced the new Millenium DXL to the world with a showing at the ASC Clubhouse followed by an evening event at Light Iron. Art Adams and I attended the latter, and all my photos are from that event.

Light Iron, a cutting-edge post-and-workflow operation expressly focused on making the most of digital cinema, was acquired by Panavision in December 2014, leading to intense speculation as to what was afoot. The Millenium DXL is a significant part of the answer; it combines Panavision’s deep understanding of optics and camera design with Light Iron’s digital grading expertise… and RED’s large-format, 8K Weapon sensor.

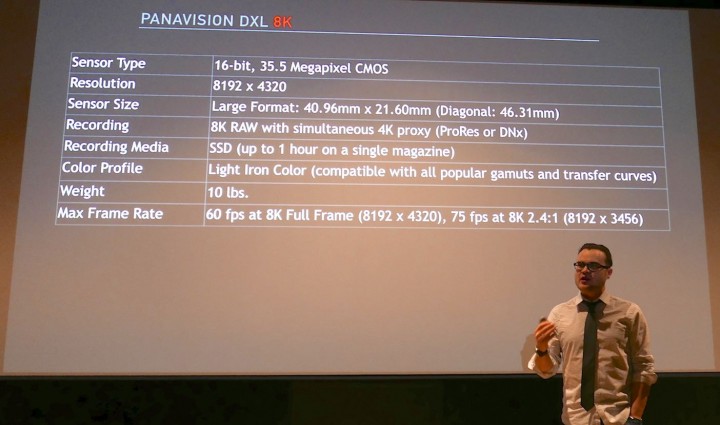

Camera Details

The DXL compares with the ARRI 65 and the Sony F65, both large-format, more-than-4K-resolution cine cameras. Like the ARRI 65, it’s a rental-only item; you’ll have to go straight to Panavision if you want to get your hands on one (this has implications for how the camera itself is designed and built, which I’ll come back to later). Panavision’s first cameras shot 65mm film (with large-format lenses to match) so the DXL is in many ways a return to form. The 40.96mm x 21.60mm sensor is about 1.8x the size of the Super35mm sensors, so to get the same angle of view you’d have with a 50mm lens on a C300, F55, Alexa, or the like, you’d use a 90mm on the DXL.

The DXL is built around the sensor, core electronics, and recording format of the RED 8K Weapon, but Light Iron has taken colorist Ian Vertovec’s experience with grading and used it to craft “Light Iron Color”, combining in-camera processing to better separate and distinguish subtle color differences so they’ll survive compression and recording, with a dedicated color science in post to get a “first light grade” straight out of REDCINE-X. The idea is to avoid having to do all the repetitive work Vertovec normally does simply to get a “cinematic” rendering out of digital files, regardless of any particular look the director and DP wish to impart; this saves time and annoyance in post as well as giving the colorist a more solid, less “muddy” image to start from. Art Adams dissects the results of this effort over at PVC, and I commend his excellent article to you.

The DXL records what are essentially bog-standard .R3D files to RED Mini-Mag SSDs. The files are said to be usable in any copy of REDCINE-X PRO, and updated versions of that program will recognize the DXL’s metadata tag and apply Light Iron Color automatically — so anyone can process the DXL’s files and get the creamy goodness of its color science (that creamy goodness is reserved for Panavision’s files; you won’t be able to apply Light Iron Color to standard Weapon clips or other RED files, which lack the complementary in-camera processing).

Current prototypes use (by most accounts) RED’s Skin Tone-Highlight “OLPF” (actually a filter pack containing color / IR filtration as well as the optical low-pass filter; it’s the color filtration that’s the important factor), but that filter pack is likely to be replaced with one designed to Panavision’s own specifications. Panavision and Light Iron will craft the filter’s spectral response to work better with their color science; their approach to color comes out of a different experiential foundation than RED’s approach (not that RED hasn’t come a long way in the past few years themselves) so their end-to-end color science will probably differ somewhat at every step of the pipeline.

Indeed, as Michael Cioni said, the images that we saw from the prototypes are “the worst DXL images we’ll ever see”; all aspects of the camera are in flux, from the color filtration to the in-camera processing to the color science in post. Many things may change before the camera goes into “mass production” — which means perhaps ten bodies overall — and becomes available for rent in early 2017.

Lensing

The DXLs use the relatively new Panavision 70 mount and accept all Primo 70 lenses. PV 70 (if I can call it that) is a “mirrorless” mount, similar to MFT or E-mount, in that it has a shallow flange depth of 40mm, allowing the rear elements of the lens to be closer to the sensor plane than if there were a flipping mirror (DSLRs) or a spinning mirror shutter (motion picture film cameras) in the way. The shallower flange depth allows a variety of optical efficiencies, leading to smaller, lighter, and better-performing lenses. By comparison, the older PV 65 mount used with other Panavision large-format lenses has a flange depth of 57.15mm; presumably a mount adapter will allow these lenses to be fitted to PV 70 cameras — and Panavision has a lot of interesting large-format glass in their inventory:

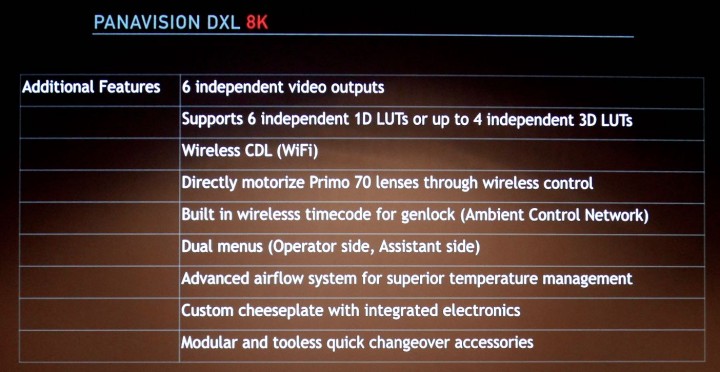

One benefit of the Primo 70s is internal motorization: focus and iris motors are built into the housings and controlled through the mount. You can stick a Preston controller (Panavised, of course!) atop the DXL and use a normal FIZ (Focus / Iris / Zoom) handset, but you don’t have those lumpy lens motors clamped to the support rods nor the rat’s nest of cabling associated with them. This speeds up camera builds, teardowns, and lens changes.

That’s one thing that Panavision’s business model enables. They don’t sell their gear, the only rent it out, so they don’t have to build it to a set price target; rather, they build it to to optimize functionality, longevity, and maintainability. That philosophy is evident throughout the camera.

Built-to-Perform, not Built-to-Sell

Cine primes with built-in motors are more expensive than cine primes without, but they’re easier and faster to swap and to use. If you’re trying to sell a motorized Primo into a market that could buy a comparable Master Prime or Cooke without a motor for a fair amount less, it’s rather hard to make the case for the Primo. But if instead you’re amortizing the cost over the life of the lens (and a well-cared-for lens can last for decades), and the internal motor makes life easier for those customers that use remote FIZ, why not?

Instead of a single control panel, the DXL has two built in, one on either side. They can be used simultaneously for different tasks, which means each has to have its own processor. The cost of the camera’s control interface is thus doubled, but it means that there’s never a need to run ‘round the other side of the camera or hand off a floating panel to change anything, and on the rare occasion that the operator and AC both need to fiddle with things, there’s no waiting involved. It may seem like a small benefit given the added expense, but it’s these small benefits that add up over a day’s work.

The DXL has six SDI outputs, all tweakable in terms of LUTs and looks. Six seems like a lot — and there’s a lot of added circuitry and expense involved to support those outputs — but Panavision figures that having that many simplifies signal distribution downstream. Again, it makes the customer’s life easier, so it’s worth doing.

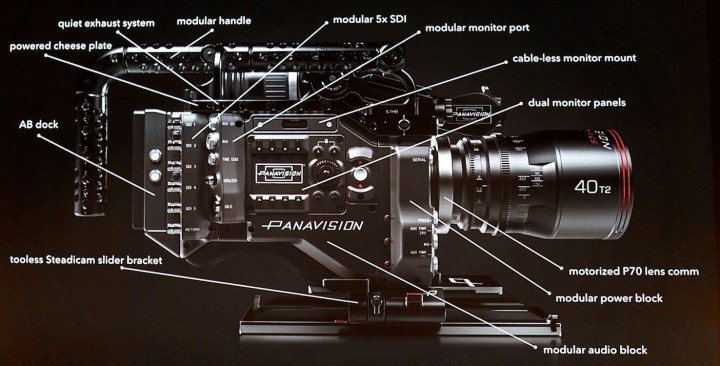

Furthermore, the whole freakin’ camera is modular, and not in the Dagwood-sandwich stackable way something like a RED Weapon or Sony F5/F55 is. The DXL is still camera-shaped, with a real shoulder mount and everything in its proper place, yet bits ‘n’ pieces can be swapped out as needed. For example, if you want to record audio on camera, there’s a roughly triangular wedge on the right side that can be replaced with XLRs. Don’t want to be bothered? Lose the audio module so those pesky soundies won’t be buzzing ‘round your camera like horseflies.

Yes, this is a very expensive way to build a camera. But it makes the customer’s life better, and it also helps Panavision out: the modular design lets Panny swap out subsystems for repairs or upgrades more easily, without having to tear down or remanufacture the entire camera. If you rent a DXL in 2017 and then rent the same serial number in 2025, there’s a very good chance it won’t be quite the same camera; it’ll have had module upgrades and transplants that make it an up-to-date 2025 model, not that sad primitive thing (in retrospect!) that you used way back in the dark days of the previous decade.

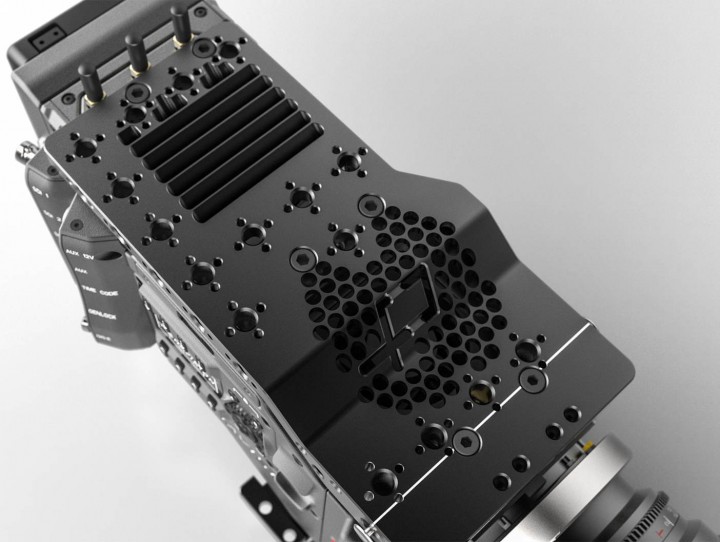

Panavision has also tweaked the camera’s cooling system. The small whining fans so familiar to RED users are gone, replaced with large, low-speed fans beneath the top cheeseplate to draw air in at the front, blow it over the sealed electronics, and exhaust it it the rear. I couldn’t hear any noise from the DXLs’ fans at Light Iron even with my head next to the camera, though to be fair, the venue was a wee bit noisier than the typical quiet set.

The DXL sits fairly naturally on the shoulder. I found that the built-up kit, with A-B battery on the back, a Preston FIZ controller, and a 65mm T2 lens, was on the front-heavy side, but at least it sits on the shoulder the way a camera should — and with more time to better adjust the EVF position, and an added front handgrip or two, I expect it would be reasonably comfortable.

Your correspondent grinning like a fool, while a worried Panavision person watches. Image courtesy Art Adams

TL;DR

Overall, it’s a highly attractive package: a large-format, high-resolution sensor; Light Iron’s color; Panavision’s legendary glass; and an operator-friendly, highly usable design wrapped around it all. Panavision is back in the game with an own-brand camera, and that’s a good thing for cinematographers.

The Perfect Circle?

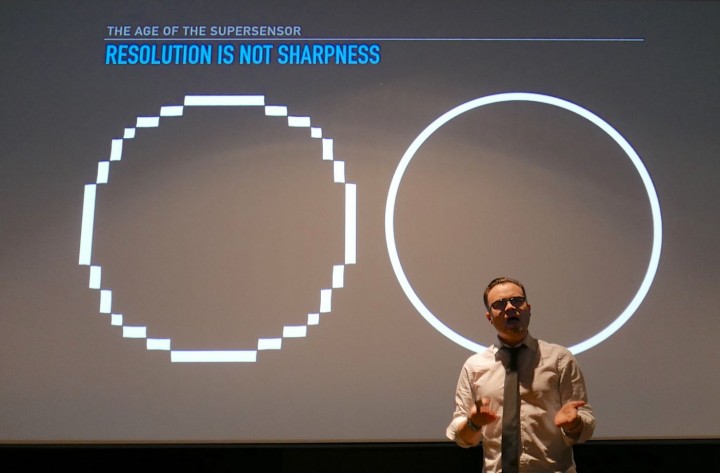

One more thing. In his presentation, Michael Cioni put forward the idea of the “perfect circle”:

The high resolution of the 8K DXL isn’t really adding “sharpness”, but “smoothness”, the point at which visible pixelization artifacts disappear. There’s plenty of sharpness already in a 4K image; what the added resolution does is add finer texture, smoother curves, and a natural fullness to the image, in contrast to sharpening the image in post. Cioni claims that the DXL is at the tipping point where images transition from looking digital to looking smoothly natural, a point that he claims magazine photographers similarly found once crossing the 30+ Megapixel barrier (the DXL’s sensor has 35.5 Megapixels).

I have two reactions to this: one, that every time we have a step change in resolution we hear something like this. HD was crisp reality compared to SD; 4K solved all the “digital look” issues of HD (and was good enough for magazine cover shots, while we’re at it); now, 8K is the point where sharp turns to smooth.

Today, 8K is as pixel-rich as mopix cameras get, and those 8K original images make for delightfully smooth and detailed 4K projected pictures. But what happens for the 2020 Olympics: won’t 16K origination provide that same, extra punch of reality for our 8K broadcast feeds?

Two, maybe he’s right: maybe 8K is the tipping point we had to get to before we stop worrying about sharpness. Certainly there was nothing to complain about in the 4K projection we saw — and Art and I, cine geeks to the end, were sitting in the front row and straining our eyeballs, looking for things to complain about.

But then again, I sit in the front row for 8K demos at NAB. 8K-native images, without the smoothness imparted by a 2x downscale, still have that digital-video look to them (that these are NHK demos in the preferred Japanese style, with lots of edge enhancement and chroma boosted to the max, probably doesn’t help). By the same token, 4K out of my lowly GH4 looks like adequate but not noteworthy 4K, yet when downsized to HD it magically transforms into really superb HD, with an unusually smooth and natural rendering.

Without in any way diminishing my respect for Mr. Cioni and for what Panavision / Light Iron / RED have accomplished, I have to politely disagree with the idea that the 8K DXL is any sort of “end of history”: when it comes to resolution, in the long run, too much is never enough. Each time we think we’re there, along comes the next step change and shows us what we’ve been missing all along.

Ain’t progress grand?

Disclosure: Panavision invited me to the press event and would have plied me with alcohol, but I was driving and had to abstain from tippling. There is no material relationship between me and Panavision, Light Iron, or RED, and no one offered any payment or special consideration for a favorable writeup.